Simmons University Center for the Study of Children's Literature presented the biennial Summer Children's Literature Institute from July 25–27, 2025. This year’s theme, “Are We There Yet?” brought an impressive array of creative writers, illustrators, publishers, and scholars to reflect and promote conversations about literature for young people.

The planning began two years ago, from obtaining permission to use art by Melissa Sweet (from How to Read a Book by Kwame Alexander, HarperCollins 2019) to designing the swag-bags and table decorations featuring the book-umbrella-carrying girl under a shower of alphabet letters.

A 50th Birthday Toast

Wicked author Gregory Maguire ’78MA began the Institute on Friday night with a toast to Barbara Harrison, the visionary who held the first Summer Institute in 1975 and launched the nation’s first Master’s of Arts degree in Children’s Literature two years later. Harrison’s attendance at this year’s Institute raised a glass of prosecco and a cupcake treat to mark the Center’s 50th birthday.

As the audience applauded the words from her original NEH grant “to elevate the stature of children’s literature as a necessary and legitimate area of academic pursuit,” current Center and graduate programs director Cathie Mercier ’84MA ‘93MPhil invited all to “take in the embodiment of what Barbara started. Imagine that each teacher, librarian, writer, illustrator, publisher, faculty, parent, aunt, uncle, grandparent, friend stands atop piles of children’s books, endless young adult narratives and verse novels, and compelling illustrations. Holding those books, you’ll discover hundreds of readers, thousands of readers, millions and billions and trillions of readers. Please raise your glass to Barbara, for this sonorous, echoic disturbance of the universe.”

Maguire, an early graduate who later taught and directed the Center, opened the Institute by weaving a tapestry of story strands. From Scheherazade’s life-saving tales to the novels of Edward Eager that Maguire read as a child, he characterized stories for children as “nourishment and consolation.”

He likened the Center for the Study of Children's Literature to “a noisy local train, full of high hopes and missionary fervor” and submitted the study of children’s literature as “a noble experiment” whose final designation is “wholly a mystery.” Perhaps, he speculated, we aren’t there yet because, as children’s literature cycles songs of innocence and suspends experience, a “there” has not yet been imagined.

Art and Story Shape a World

In her presentation on depictions of the earth and climate change in international children’s picturebooks, 2025 Carol S. Kline Visiting Instructor Lauren Rizzuto ’11MA surveyed decades of historical movements and picturebook responses, including capitalism, civil rights, the Vietnam War, the rise of Planned Parenthood, and the impact of colonial displacement, along with emerging studies of marginalized historical perspectives in the 1970s.

Rizzuto highlighted the need for more “earth-centric” picturebooks that don’t conform to common, oversimplified narratives asserting that human destruction of the earth can be undone if the young people just learn how to garden. She argued that less familiar narratives advance less comfort as they yield “reflection as well as critique of nostalgic idealism.” Picturebooks stand a unique opportunity because, by convention and design, they operate as a dialogic form that engages the breader and book as co-creators, child and adult and collaborators in finding “creative solutions to confront climate change.”

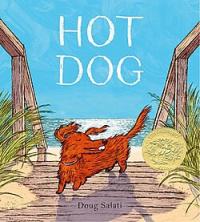

Doug Salati, author/illustrator of the Caldecott-winning Hot Dog (Knopf Books for Young Readers, 2023) and Rotem Moscovich ’06MA, Editorial Director of Picturebooks at Knopf, detailed their editorial process in Salati’s story of an overheated dachshund. Thumbnail sketches Salati made after a trip to Fire Island inspired a series of 13 dummies that would eventually become Hot Dog.

“Maybe I needed to do them all to come back to the thing that really stuck,” Salati noted. Moscovich observed that “iteration is the key.” As Salati moved things around and tried to find the solution to a “big puzzle,” he listened to suggestions about pacing, movement across the page, beginnings and endings. Through them all, his sketchbook served as an invaluable archive of past ideas that could be put to a new purpose.

Honest Voices in Art and Text

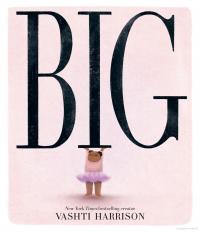

Vashti Harrison, author and illustrator of the Little Leaders series (Little, Brown, 2017) and the Caldecott-medal winning Big (Little, Brown, 2023), engaged in conversation with Breanna J. McDaniel ’14MA, who won the 2025 Ezra Jack Keats Writer Award for Go Forth and Tell: The Life of Augusta Baker, Librarian and Master Storyteller (Dial Books, 2024). Their collaboration stressed “the artist’s duty…is to reflect the times.” (Nina Simone, c.1965).

Harrison’s Little Leaders series was in response to a drawing challenge for Black History Month as she grappled with whether her work could make a difference given the struggles facing the African American community. From innovative page compositions, a precise color palette, and animated use of type font, she hopes that her art “elicits an emotion.” With the complementarity of art and text, she makes the radical choice to present hope and show children with agency.

McDaniel, who reached for a hopeful perspective throughout the 17 drafts of her first picturebook, Hands Up! (illustrated by Shane W. Evans, Penguin Young Readers Group, 2019), found comfort by connecting with the kids in her life. “I was able to recover some of that hope and peace, to pause in the wake and waiting.” As collaborators, Harrison and McDaniel hear hurt and convey joy.

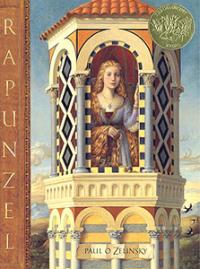

Paul O. Zelinsky, winner of three Caldecott honors and the 1998 Caldecott Medal for his illustrated retelling of Rapunzel (Dutton Press, 1997), toured his highly eclectic approach to illustrating his own and others’ picturebooks. Whether inspired by Renaissance oil paintings or playing with fantastical digital art, Zelinsky always “transforms his art to best fit the narrative,” said Ellen Keiter, former Chief Curator at the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art.

Keiter pointed out the intuitive nature of Zelinsky’s varied approaches, whether he was experimenting with a folk art influence and painting on the thinnest pieces of wood for Swamp Angel (written by Anne Isaacs, Puffin Books, 2000) or experimenting with Photoshop. Much like his earlier oil paintings, the art he makes on a digital tablet enables layering of transparent color for maximum effect.

Complexity and Ambiguity

Beatriz Gutiérrez Hernández, author/illustrator of the Ezra Jack Keats Honor book Benito Juárez Fights for Justice (Godwin Books, 2023), shared the process of writing and illustrating Pearls in the Sand: Protecting Sea Turtles in Oaxaca (Godwin Books, 2025). The book was inspired by a visit to the Oaxacan coast, where she participated in an “integration event” and scooped tiny sea turtle hatchlings into coconut shells and carried them to the shore.

Focused initially on the ecological impact of losing these creatures, Hernández learned the unexpected consequences of the 1990 ban on turtle hunting and egg poaching that caused ripples of economic hardship for the surrounding community. The epiphany called her to overtly weave together conservation work with the displacement concerns. Hernández endeavors to “share stories of marginalized communities that are constructive, not reductive,” while acknowledging the complex ecosystem of nature, culture, policy, and economy.

The Mary Nagel Sweetser Lecturer, award-winning illustrator Christopher Myers, earned a Caldecott Honor for Harlem (written by Walter Dean Myers, Scholastic, 1997) and the Coretta Scott King Award for Firebird (written by Misty Copeland, G.P. Putnam's Sons Books for Young Readers, 2014). A multimedia artist, Myers is the Creative Director of Make Me a World, an imprint of Random House dedicated to “exploring the vast possibilities of contemporary childhood.”

His evening talk decried ignorance as “an excuse not to listen to each other” and avoiding frank conversations about our beliefs. He points to the use of “shibboleth” in popular discourse, words used as a litmus test of cultural and political belief, while losing sense of the values underpinning the original meaning.

“Every child should be treated like they can change the world — and they will,” said Myers, who sees children’s literature as “the one place where we are constantly in conversation with each other.” He called for the field to learn how to invite ambiguity to give readers space to enter into conversation, to ask questions, explore values, and build trust.

Non-Western Narratives

Muscogee Nation Citizen Cynthia Leitich Smith is an author and curator of Heartdrum, a HarperCollins imprint that centers Indigenous experiences. She cheers current authors who shift “the narrative from speaking of us in the past tense to casting us in the present and future.”

Leitich Smith recalled her childhood disappointment in the representation of Indigenous characters that led her to avoid them altogether. In traditional publishing, she found that if a story didn’t fit a stereotype, those outside the indigenous community assessed it as inauthentic; editors deemed her novel about an indigenous girl who became a lawyer – Leitich Smith’s own career path – as too “aspirational.” She brought attention to distinctive cadence and patterns in language and storytelling that permeate and resound an oral tradition.

Adib Khorram, author of the award-winning Darius the Great is Not Okay (Dial Books, 2018), shared his perspective as an Iranian/American in the diaspora. “I sent Darius on a trip that I wanted to take and may never be able to take,” he noted, given Iran’s criminalization of queerness. Khorram has learned about Iran from family photos and reports from those who have visited, and faces the idealized Iran vs. the reality of the people living there.

To live in diaspora, he said, is “to long for a home that no longer quite exists, if it ever did.” In striving to “write books that let children feel seen and to understand their world,” he channels experience to transmit a genuine scene of an Iranian grandmother accepting her gay grandson; this is the truth he wants for all queer children.

Lisa Yee, author of Newbery Honor Book, Asian/Pacific American Children’s Literature Award and National Book Award Finalist, Maizy Chen’s Last Chance (Random House, 2022), began her writing career with the Red Lobster drinks menu, then television commercials, and content for Disney. An inveterate outliner and “stealer” of overheard conversations, Yee advises authors to “lead with character and story.” When hate crimes against Asian Americans surged during the pandemic, Yee found a way out of her first writer’s block by balancing instances of anti-Asian sentiment with community and hope.

A Safe Space for Big Emotions

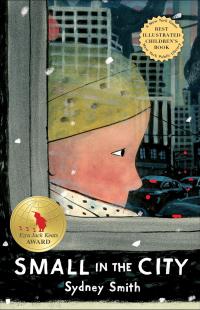

The legendary Neal Porter, Publisher Emeritus of his own imprint at Holiday House, joined Hans Christian Andersen author/illustrator Sydney Smith in a conversation that revealed their creative partnership. Smith recalled sharing with Porter an idea for his first authored and illustrated picturebook: a meditation on the quiet solitude of the city in winter. Porter suggested he add a dog. Smith wanted to ignore it, but he couldn’t quite shake the idea — even if he substituted a cat. The resulting Small in the City (Neal Porter Books, 2019) adopts the unconventional second-person point of view to address the reader — and then flips the expected story arc. For Porter, the shift heightens the reader’s engagement and holds them in an emotional grasp.

Smith’s collaboration with author Jordan Scott, I Talk Like a River (Neal Porter Books, 2025), includes a gatefold opening showing the back of the main character as he enters a glittering, always moving river that represents his disfluency. For Smith, the gatefold immersed both the child and the reader in the realization that “they’re not broken.”

Echoing Salati before him, Smith described his process as iterative with occasional sudden bursts. Smith reflects on his role as a picturebook creator as one that facilitates reading together “a sacred gesture of love” and a safe space for children to process complicated emotions.

The program included eight professionals who teach in the children’s literature programs who offered seminars on topics such as favorite children’s books, the Golden Age of Children’s Literature (mid-19th to early 20th century), zine-making, and the diversification of children’s publishing. In addition, a craft room invited attendees to create bookish umbrellas and zine pages that document this 50th birthday year. Chalene Riser ’20MA and Bethany Campbell ’21MAMS assisted throughout the weekend. The Frugal Bookstore, a Black-owned independent bookstore based in Roxbury, set up a shop adjacent to the Paresky to sell books by all participating speakers.

Mercier, who included ‘easter egg’ references to previous Institutes in her remarks throughout the weekend, closed the Institute by encouraging attendees to “linger not in answers, but in the interstices of ‘Are we there yet?’ Who are we? When does there become here? And how does ‘yet’ invite ambiguity, catharsis, imaginative possibility, radical hope?”

As the Center for the Study of Children's Literature sails into its 51st year, we thank all who have contributed to the endowed fund to support a professorship in Children’s Literature. Haven’t donated yet, or want to make a pledge (email [email protected] for a pledge form) or estate gift? Each contribution lights another candle illuminating our goal of an Endowed Chair in Children’s Literature — the best birthday present ever.