Centered around the exploration of important themes and issues, the fall Community Read is designed to engage the campus community, generate robust discussions, and foster the exchange of diverse ideas and perspectives.

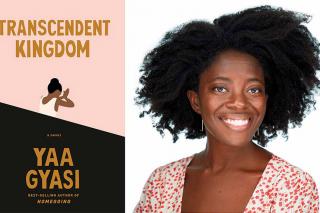

President Wooten shares her takeaways from this fall’s Community Read, Transcendent Kingdom. Yaa Gyasi's powerful novel serves as a moving portrait of a Ghanaian immigrant family as they grapple with faith, science, religion, and love.

1. Gyasi’s setting of Huntsville, Alabama is a microcosm of racism against Black Americans.

Despite the fact that opioid addiction spans race, class and age, Nana’s addiction is viewed as inevitable in the eyes of their white, evangelical church community (pg. 172-173). Throughout the novel, Gyasi illustrates the racial underpinnings of the church, the community’s valuation of Nana’s athleticism over his wellbeing, and the countless microaggressions and racist acts the family encountered in their community.

“But the memory lingered, the lesson I have never quite been able to shake: that I would always have something to prove and that nothing but blazing brilliance would be enough to prove it.” Page 61

2. The impact of internalized racism.

The pressures of institutionalized racism wreak havoc on Gifty and her family. From her father’s abandonment to her brother’s addiction and death, the trauma severely impacts Gifty’s view of herself and ability to form genuine relationships.

“But walking around with my father, she’d seen how America changed around big black men. She saw him try to shrink to size, his long, proud back hunched as he walked… Homesick, humiliated, he stopped leaving the house.” Page 27

“In that moment, and for the first time in my life really, I hated Nana so completely. I hated him, and I hated myself.” Page 173

3. Gifty’s mother’s identity in relation to her language.

Gifty depicts her mother’s different identities through her language: “giggling and gossiping” in Fante with friends, Twi to her children as an authoritative but warm mother figure, and timid English when navigating white America. This identity shift illustrates her mother’s lack of confidence and embarrassment as a Black immigrant woman.

“There were other moments like this, where the woman whom I thought of in my head shrank down to someone I could hardly recognize. And I don’t think she did this because she wanted to. I think, rather, that she just never figured out how to translate who she really was into this new language.” Page 129

4. Gifty’s relentless search for the soul and salvation through science.

Throughout the novel, Gifty reveres her experiments with mice, describing them as “if not holy, then at least sacrosanct” (Pg. 92). When the church and her faith are unable to help Gifty understand her brother’s addiction, she turns to science. Through Gifty’s work in neuroscience, she attempts to seek meaning and salvation from her life’s tragedies.

“I had traded the Pentecostalism of my childhood for this new religion, this new quest, knowing that I would never fully know.” Page 21

“... the more I do this work, the more I believe in a kind of holiness in our connection to everything on Earth. Holy is the mouse. Holy is the grain the mouse eats. Holy is the seed. Holy are we.” Page 92

5. The juxtaposition of Gifty’s defense of religion to her work as a scientist.

Although Gifty no longer believes in God, religion remains important to her because she associates faith with her mother. As an undergraduate at Harvard, Gifty others herself from her classmates when she defends the merits of religion. Later, Gifty ultimately realizes that faith and science do not have to be mutually exclusive, as neither can answer all of life’s questions.

“...I had already exposed myself. A backwoods bama, a Bible thumper… my small group didn’t bother hiding their disdain for me... After all, what could a Jesus freak know about science?” Page 89

“But this tension, this idea that one must necessarily choose between science and religion, is false. I used to see the world through a God lens, and when that lens clouded, I turned to science. Both became, for me, valuable ways of seeing, but ultimately both have failed to fully satisfy in their aim: to make clear, to make meaning.” Page 198