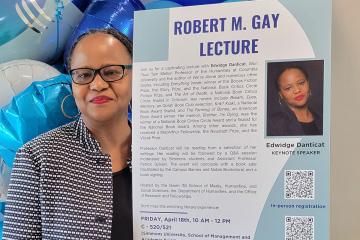

Simmons hosted the annual Robert M. Gay Memorial Lecture on April 18. This year’s distinguished speaker was Edwidge Danticat, award-winning author and the Wun Tsun Tam Mellon Professor of the Humanities in the Department of African American and African Diaspora Studies at Columbia University. Danticat read excerpts from her recent work and engaged the Simmons community in a conversation about solitude, community, and memory. The event concluded with a book sale and signing.

Established in 1964 by Simmons alumnae/i Eleanor Bates ’39, Miriam Gosian Madfis ’40, and Dorothy Gove Russell ’32, the annual Robert M. Gay Memorial Lecture brings distinguished guest scholars to Simmons for an inspiring lecture and conversation. Hosted by Simmons’ Department of Humanities and co-sponsored by the Gwen Ifill School of Media, Humanities, and Social Sciences and the Office of Research and Fellowships, this event honors the legacy of Professor Robert. M. Gay, (1879–1961), a longtime Simmons faculty member who founded the English Department in 1930.

Following a warm greeting by the Ifill School’s Dean Dr. Ammina Kothari, Wanda Torres Gregory, Professor and Chair of the Department of Humanities, spoke about the contributions and legacy of Professor Robert M. Gay. In addition to his teaching and leadership roles, Gay was an accomplished scholar who published numerous books, including Emerson: A Study of the Poet as Seer (1928) and a volume of essays entitled Another Look at Women’s Education (1955).

Assistant Professor Patrick Sylvain from the Department of Humanities introduced this year’s guest speaker, Edwidge Danticat, the Wun Tsun Tam Mellon Professor of the Humanities at Columbia University and award-winning author of several novels, essay collections, and memoirs.

Most recently, Danticat published a book of essays entitled We’re Alone (Graywolf Press, 2024). Earlier works include Everything Inside (Knopf Doubleday, 2019), winner of the Bocas Fiction Prize, the Story Prize, and the National Book Critics Circle Fiction Prize, and The Art of Death (Graywolf Press, 2017), a National Book Critics Circle finalist in Criticism. Her novels include Breath, Eyes, Memory (Soho Press, 1994), an Oprah Book Club selection, Krik? Krak! (Soho Press, 1995), a National Book Award finalist, and The Farming of the Bones (Soho Press, 1998), an American Book Award winner. Her memoir, Brother, I’m Dying (Knopf, 2007), was the winner of a National Book Critics Circle Award and a finalist for the National Book Award. Among other awards, she has received a MacArthur Fellowship, the Neustadt Prize, and the Vilcek Prize.

Writing with Integrity

Professor Sylvain, a friend and colleague of Danticat, offered personal anecdotes of their first encounters with one another. In 1993, Sylvain received a manuscript of Danticat’s first novel from Ntozake Shange (1948–2018), a celebrated Black feminist poet and playwright with whom Sylvain socialized through a prominent community of Black writers known as the Dark Room Collective. After reading Danticat’s early writings, Sylvain said, “I was overwhelmed by it, and I said to Shange that she will be a major voice in Haitian literature.”

According to Sylvain, Danticat’s breakout book, Breath, Eyes, Memory (Soho Press, 1994), established the author “as a significant literary voice.” This novel, Sylvain continued, offers a profound examination of “motherhood, intergenerational trauma, and the cultural constraints placed upon women’s bodies.”

Since then, Danticat’s short stories, novels, memoirs, and essays have, for Sylvain, “profoundly influenced contemporary literature through evocative portrayals of Haitian life, diasporic identity, memory, trauma, and resistance. In a sense, [there is] hope as well … if you read her work carefully.”

Danticat’s later works probe colonization, the political turbulence of Haiti, and the immigrant experience — she was born in Port-au-Prince and migrated to the US at the age of 12. Herein, Sylvain explained, storytelling functions as modalities of empathy, resilience, and healing.

For Sylvain, one of the most salient aspects of Danticat’s style is integrity. “As a writer, particularly in this current moment, when intellectuals and writers are being indirectly and directly persecuted, [the truth, as opposed to alternative truths] is very important,” he said, emphasizing that Danticat’s works do not shy away from the truth.

Being Alone Together

Assuming the podium, Professor Danticat gave the audience a bilingual greeting in Haitian Creole and English, which conjured an atmosphere of honor and respect. “It sounds like Professor Gay was someone who explored writing, especially through … writings,” she said. “And I am a big reader of writings on writing, so I am appreciative of that.”

Referencing her most recent book, We’re Alone (Graywolf Press, 2024), Danticat began by explaining the meaning of its title. “This sounds contrary to what I practice and believe, for we are never in fact alone; our ancestors are with us, and we are always in community,” she said.

However, Danticat’s understanding of being alone was in part inspired by the Haitian-American anthropologist Dr. Gina Athena Ulysse, and specifically her concept of rasanblaj — “an assembly, compilation, enlisting, [or] regrouping of people, spirits, things, [and] ideas.” As Danticat noted, “I think that Professor Gay would have appreciated this idea, about writers and readers meeting … in some intimate spaces where we are all alone.”

Danticat proceeded to read excerpts from the preface to We’re Alone, which begins with verses from a Haitian poem called “Plage” by Roland Chassange. (Danticat first encountered this poem in a 1934 English translation of Haitian poetry).

“Some of the poems of the [1934] collection felt intimate, particularly those of Roland Chassange, whose words read like secrets,” Danticat writes. “We’re alone is of course the persistent chorus of the deserted, as in, no one is coming to save us. Yet, we’re alone can also be a promise that writers make to their readers; a reminder of the singular intimacy between us. At least we are alone together.”

For Danticat, writing, and particularly writing essays, constitutes a quest for aloneness and togetherness between writers and readers. Here Ulysse’s idea of rasanblaj comes into play.

For instance, Danticat recounted how Chassange was arrested by François Duvalier’s dictatorial regime in 1963 for possessing “contraband literature” (he worked at a publishing house), after which he was never heard from again. Eventually, Danticat located his granddaughter, Régine Chassange, one of the lead singers of the Indie rock group Arcade Fire, who supplied Danticat with the original Haitian Creole version of “Plage.”

Danticat then read Chassange’s poem, in Haitian Creole and English, to the Simmons community:

Allow me to take you by the hand

and tell you some simple

and unforgettable things …

Because we were alone,

near the shore, under this canopy

of palms, and we loved each other,

the pleasure was intense and

indescribable.

These words, for Danticat, demonstrate how “writers die, but not their canopy of language. Just as Roland Chassange still sometimes whispers to me … dear reader, please allow for me to reach for your hand, we are alone.”

Giving Voice to Pain

In another reading from We’re Alone, Danticat addressed the topics of climate change and mass migration. She referenced a United Nations report surmising that by 2050, approximately one-quarter of a billion people will be displaced due to rising sea levels, droughts, wildfires, extreme heat, and floods.

Danticat described this harrowing predicament: “A migrating nation with no land mass, borders, railways, roadways, seaports, airports, schools, hospitals, communications, financial institutions, or disaster management systems — all of which they will need to acquire from the other nations that have somehow managed to escape their fate.”

Moreover, Danticat suggested that the “unwanted citizens” of this “pariah state” will be subjected to smuggling, trafficking, policing, and abuse, and many will perish of thirst, hunger, drowning, or neglect. “Few countries will want to embrace or absorb this populace, yet no fences, walls, or armies will chase them back,” she writes. “They will be migrating not to chase dreams or procure luxuries, but for food and water.”

Danticat channeled Haitian writer René Depestre (b. 1926), specifically his poem “The River” (La Rivière), which presciently links water, the unknown, migration, and sorrow.

Another source of inspiration for We’re Alone, Danticat recounted, came from a syllabus for a summer 2020 course on essay writing, entitled “Writing the Self,” which her daughter Mira took online.

Taught by writer Erica N. Cardwell, Danticat and her daughter were “won over” by the course description: “Imagine ‘The Essay’ is a body of water — far-flung and teeming into the distance. And you, the writer, are alone on the shore. Will you enter the water? And if so, how will you swim? Or will you stand on the shore as the water splashes against your ankles?”

Decoding Cardwell’s words, Danticat referenced reflections by poets Adrienne Rich (1929–2012) and Audre Lorde (1934–1992) on the importance of speaking through pain and giving voice to those who have been silenced. Danticat concluded her lecture by reprising lines from Chassange’s “Plage.”

The Power of Storytelling

Sylvain began the post-lecture discussion with Danticat, first inquiring about her use of intertextuality (i.e., referring to past authors and texts).

“I think of this kind of intertextuality ancestrally, in the sense that we are all a part of a lineage,” Danticat responded. “And my lineage is vast. When I read some words, I feel that I am in an immediate conversation with that writer. Again, it’s like we are alone [together.]” She added that, as a more introverted person and as a writer, solitude can be “blissful.”

Sylvain noted how Danticat weaves diverse histories and perspectives into her novels. In essays and fiction, Danticat said, “my primary goal is always to tell a story, and an engaging kind of story. And it’s probably because I grew up at … the feet of storytellers, more oral storytelling, so it was very active engagement.” For her, these “micro” narratives coalesce to form a larger story or history.

Responding to what she tries to solve in her writings, Danticat highlighted self-discovery. “This lecture is named after someone [Robert M. Gay] who wrote about writing,” she said. “One way [to do this] is more like a quest or exploration … And I think that is the nature of life in general, that’s why we have existence.” Essentially, Danticat approaches writing and stories as a way to make sense of the circumstances that surround us.

With members of the audience, Danticat discussed creating an impact through writing, the utility of boredom, finding community with other writers, and Afro-Caribbean concepts of time. Speaking to the several Caribbean authors in attendance, Danticat advised attendees to write their own truths and to privilege memory over erasure.

“I’m never really alone,” said Danticat. “I always tell people that I am a voice in a chorus.” Even when writing about trauma and violence, she said, tapping into pain can make for the best writing. “Go deeper [into the pain], because that’s where the truth is.”