“Feminists and postmodernists have challenged the constructions of gender on the basis of biological differences. Ancient Chinese medicine echoes this view of gender as non-binary,” says Assistant Professor of History Yunxin Li. “According to medical practitioners and theorists in ancient China, yin and yang are not mutually exclusive categories. Rather, they can manifest themselves in varying gradations in the human body.”

In her recent article, “Representations of Gender in Early Chinese Medicine: A Prehistory of Fuke” (published in The Bulletin of the Jao Tsung-I Academy of Sinology), Li explores the relationship between medical knowledge and gender relations in ancient China. In doing so, she uncovers a fascinating history of malleable gender categories, ancient gynecology, and women healers.

A Brief History of Chinese Medicine

Li, who specializes in the history of the Han Dynasty (c. 202 BCE–220 ACE), recounts that what is now known as “traditional Chinese medicine” has changed over the centuries. In the ancient context, China formulated three branches of medicine.

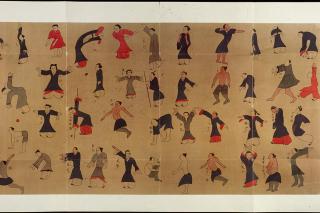

The first branch of medicine, “nourishing of life,” emphasizes diet, daily breathing, and stretching exercises. “These practices were generally aimed at keeping one healthy, and the focus was preventative rather than curative,” says Li.

The second variant, technical medicine, was based on vessel theory. “These theorists focused on qi (energy or air) and its circulation through the vessels of the human body,” explains Li. “If qi flows smoothly, then your body is healthy, but if qi is blocked then one becomes sick.”

The third branch, pharmacopeia, “refers to the recipe books that provide lists of prescriptions for specific diseases. These treatments were often derived from traditional herbs,” explains Li.

Li’s research also examines the impact of Chinese religion on medicine. For instance, medical texts often explain how exorcism constituted a method for curing diseases believed to have been caused by evil spirits.

From the perspective of gender, the foundational concept of yin / yang became integrated into medical literature and knowledge. (The Chinese terms yin and yang are distinctly rooted in Chinese culture, and are, therefore, untranslatable). Supposedly coined by the philosopher Zou Yan (d. 240 BCE), yin and yang were considered cosmological forces that are opposite, yet complementary. “For example, many pairs of natural phenomena (such as night and day, moon and sun, female and male) were mapped onto yin and yang,” says Li.

“Generally speaking, the feminine is yin and the masculine is yang,” says Li. “And male intellectuals often cited the yin / yang theory to justify unequal gender relations. For instance, they argued that a wife should be submissive to her husband because she is yin, and the husband should dominate her because he is yang.”

However, yin and yang were not fixed categories in Chinese medicine. Instead, they operated along a spectrum and were often in flux. “Medical authors did not see anatomical differences as the most fundamental. Instead, they interpreted anatomical differences as results of the flow of qi in the vessels,” explains Li. Chinese medical literature reveals that female bodies could encompass sections of both yin and yang. Elsewhere, extreme yin could transform into yang, and vice versa. “Therefore, yin and yang are relational terms; they come in pairs and can shift depending on the circumstances and context,” she concludes.

Women’s Medicine in Premodern China

In ancient China, a specialized branch of medicine for women was called fuke, which loosely corresponds to gynecology and obstetrics in today’s Western medicine. “Fuke assumed that the female body required customized care. Certain doctors specialized in treating women with health issues related to menstruation, pregnancy, and childbirth,” says Li.

Most scholars concede that fuke was established during the Song Dynasty (960–1279). However, Li has observed gender-specific diagnosis and treatment in earlier sources. “I argue that medicine for women can be traced further back to the Han and pre-Han periods. Even if these earlier texts are less systematic than those from later periods, fuke had a longer prehistory than is generally recognized.”

Within the arena of fuke, Li’s research demonstrates that ancient medical texts, such as Recipes for Fifty-Two Ailments (c. 215 BCE), have an interesting approach to menstruation. For example, medicinal recipes from this text use women’s menstrual cloth to create curative potions. “The medicinal properties of menstrual blood were quite diverse,” explains Li. “It could treat spasms [in humans] caused by horses, intestinal swelling, and other ailments.”

The healing properties of menstrual blood in ancient China resonate with anthropological studies on tribal cultures and premodern societies, Li finds. “In cultures beyond China, menstrual blood had a magical connotation. But menstrual blood could also be taboo, as people believed it could contaminate those who came into contact with it. Thus, menstrual blood evoked both fear and power. In Chinese history, I have observed that the healing effects of menstrual blood seem to emerge out of the power of pollution,” she says.

Female Practitioners of Medicine

In her research, Li also finds evidence of female practitioners of ancient Chinese medicine. “Early Chinese recipes mention the female shaman, who was basically a healer. These women performed incantations and exorcisms to help ward off evil spirits. Female caretakers and midwives also appear in early Chinese histories and legal cases that required physical examination.”

Although most doctors in ancient China were men, two female doctors are included in the official histories of the Han Dynasty, as they both served the royal family. During this period, there were no medical schools; medical knowledge was transmitted from teacher to pupil in an exclusive (i.e., non-public) setting. “Medicine was considered an esoteric skill, and it was said that some of the most famous doctors learned it under secret or mysterious circumstances,” explains Li. “Given women’s familial duties, it would be hard for them to travel and learn medicine from the masters. Thus, I surmise that female doctors obtained medical knowledge from their own family members.”

As technical medicine became more mainstream, the field also became more male-dominated. “In texts like The Yellow Emperor’s Inner Canon (c. 111 CE), there is more emphasis on pathology. In other words, Chinese medicine became more diagnostic, focusing on treatment rather than prevention. This shift was ultimately disempowering for women in the medical profession. Due to women’s lack of access to medical training and education, they could not easily attain the high levels of literacy that technical medicine demanded,” says Li. “Moreover, the doctors who adopted technical medicine viewed certain healing practices — like exorcism — as illegitimate ways of treating diseases. By the period of the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), male authors critiqued female shamans and midwives for their lack of medical knowledge. While female shamans did not disappear, they were criticized and marginalized, whereas technical medicine became the more dominant branch of Chinese medicine.”

Today, traditional Chinese medicine remains, but it has become integrated with Western medicine. “Chinese medical practitioners may diagnose conditions with X-rays and other modern technologies, and prescribe modern pharmaceuticals as well as traditional herbs. Even now, people still discuss yin and yang when analyzing gender differences,” says Li.

Valuing Women’s and Gender History

As feminist scholarship has shown, the history of women and gender offers a different perspective from that of more traditional, male-dominated histories. “People have different experiences based on their gender,” says Li. “If we want to understand a greater variety of human experiences, then we cannot ignore women.” She also believes that studying concepts of gender from the past gives us a better grasp of the historical origins of today’s gender norms. By extension, we may use this knowledge to formulate gender equity in our contemporary moment.

This Women’s History Month, Li will be focused on women’s reproductive health. “The current trend of restricting women’s abortion and reproductive rights is concerning,” says Li. “If a woman cannot control her reproduction, then she loses most of the control over her life. When I reflect on premodern China, I realize that many women died during childbirth or had lasting illnesses because they did not have birth control measures.”

Li is also giving much thought to women’s mental health: “Ancient Chinese doctors were already aware that certain diseases — and especially those in women, who were considered more emotionally complex — could be caused by emotions, such as stress and anxiety, which today we identify as mental health issues,” explains Li. “I want to shed light on these issues, because they deserve the attention of women and everyone around them.”