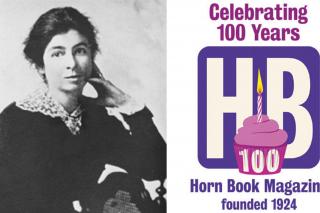

In October of 1924, the first issue of The Horn Book magazine appeared. It began as a newsletter from the Bookshop for Boys and Girls, one of the first children’s book shops in the United States, established in 1916 by the Women’s Educational and Industrial Union. Bertha E. Mahony (later Bertha Mahony Miller), who graduated from Simmons School of Secretarial Studies in 1906, helmed both the shop and the magazine. For ten years before the Bookshop was established, Mahony had been a staff member for the Union, promoting and supporting Boston’s working women.

The title of The Horn Book is a nod to classic horn books, which were used as reading primers for children, while also invoking horn imagery from The Three Jovial Huntsmen, by Randolph Caldecott (of the Caldecott Medal, awarded annually to the most distinguished American picture book for children by the American Library Association). In her first editorial, Mahony explained the purpose of the publication, as well as another meaning of the name: “First of all, however, we are publishing this sheet to blow the horn for fine books for boys and girls — their authors, their illustrators, and their publishers. Small and inconspicuous space in the welter of present-day printing is given to the description and criticism of these books, and yet the finest type of writing, illustrating, and printing goes into them.”

From this simple beginning, we now have a publication that has generated reviews, opinions, granted awards, and garnered well-deserved attention to the best books for children over the past 100 years.

The Bookshop for Boys and Girls

The necessity of such focus on literature for children was paramount to Mahony. Described by Barbara Bader in “Realms of Gold and Granite“ (The Horn Book Magazine, September/October 1999) as “a serious, ambitious reader, [Mahony] would have liked to study librarianship years earlier at the new Simmons College [now Simmons University], but lack of sufficient funds steered her toward the shorter secretarial course instead.” After completing her coursework at Simmons, Mahony became Assistant Secretary at the Union, where she launched her own initiative in a four-year series of children’s plays. She eventually persuaded the Officers and Board of the Union to finance a children’s bookshop.

Though she didn’t have a degree in Library and Information Science, Mahony sought the expert advice of children’s literature experts in her bookshop endeavor. She reached out to librarians at the Boston Public Library who offered recommended book lists. She visited the Central Children’s Room at the New York Public Library, where she met Anne Carroll Moore, first Superintendent of Children’s Work (1906–1941). She worked with Elinor Whitney (later Field) who graduated from the Library and Information Science program at Simmons in 1912. Mahony, Whitney, and their staff “promoted children’s books brilliantly,” says Bader, “with a variety of programs, exhibits, and special services, and a handsome, 110-page booklist…that was free to all comers and all correspondents.” In 1921, the Bookshop moved to a larger space with street access and a sign over the door that read, “The Bookshop for Boys and Girls — With Books on Many Subjects for Grown-Ups.”

In “The Bookshop That Is Bertha Mahony” (The Atlantic Monthly, 1929), Alice Jordan, [Boston Public Library Children’s Librarian and frequent Horn Book contributor], wrote that Mahony “brought to the task of organization an active and resourceful mind, quick to see relationships between children and books, between books and art and nature.” The shop itself was used as an exhibition space for artists, illustrators, and children, and its exhibits were often listed in the newspapers alongside prestigious galleries. In this, and many other ways, children were able to shape the Bookshop. Jordan wrote, “Often, after a summer in the country, there is a display of nature notebooks and outdoor collections, blue prints of flowers, and other projects of young naturalists.”

The writers, illustrators, and publishers of the day communicated with Mahony, understanding her sincere interest in their work. The Bookshop had, as Jordan said, “become a centre for those who choose to take children's books seriously as a branch of literature.”

The Horn Book Magazine

The Horn Book Magazine was, Bader said, “an expression, and extension, of the Bookshop itself. A grander way, prospectively, to blow the horn for good books.”

The Magazine also featured articles written by Alice-Heidi, the doll that lived in the Bookshop, most likely written by Mahony. “Alice-Heidi loved meeting the children of the Bookshop and recommending new titles for them to read,” says Renee Runge ’24MAMFA, 2024 Horn Book Fellow, in her article about the doll. “It is said that Alice-Heidi received her name, with contribution from the child patrons of the Bookshop, after Alice from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), and Heidi from Heidi (1880).”

Elissa Gershowitz ’00MA, editor-in-chief of The Horn Book, notes that, “the fields of children’s publishing and children’s librarianship became popular and vibrant at the same time that the Bookshop and The Horn Book were growing up.” Gershowitz holds a Master’s in Children’s Literature from Simmons, which itself is celebrating 50 years of operation. “The magazine came directly from the Bookshop, for people who couldn’t come to Boston to visit the store in person. [Mahony] wanted to share her book recommendations.”

Now celebrating its centennial year, The Horn Book will publish special themed issues throughout 2024, tied to topics spanning the history of children’s literature. As for Gershowitz, the collection proves tantalizing. “When I open it up, I’m lost in there for days,” she says, gesturing toward bound volumes of past issues on her bookshelves. “The best experience is to pull them off the shelf and read them, to see what people were concerned with at different points in history,” says Gershowitz. “There are still issues that we’re trying to address, like the need for diverse books. This has been a constant, though for years the issue was all but ignored.”

Gershowitz can all too easily see the parallels between Mahony’s Boston and the current era. At a recent panel about banned books held at the West Roxbury Branch of the Boston Public Library, Gershowitz recalls a panelist who talked about “the finger-wagging Boston organizations [in the 1920s] trying to censor and ban books, and the bookstores that were rebelling. Censorship never goes away, there have always been people trying to direct what children — their own children and other people’s children — can read.”

If the censors are always present, the rebels are, too. While censors threatened with book bans, Mahony devised a way to spread the importance of children’s literature across New England. “Bertha set up a bookmobile,” says Gershowitz. “Two young women drove around New England, delivering books. They took their roles seriously.”

The Caravan

With the Caravan, as it was called, Mahony’s goal was to get books into the hands of people who may otherwise lack access. Each day of the “tour,” the two staff members set up shop, recording their locations in a diary of the trip: near a post office in Ogunquit, Maine, or a blacksmith shop in Kennebunkport.

In “Treasure Island by the Roadside” (Horn Book magazine, 1999), Bader wrote, “To Mahony’s regret, the Caravan had to stop at many ‘fine summer places’ — seashore and mountain resorts — to provide dollars-and-cents returns to the sponsoring publishers. What was the value of taking books to people who took books for granted? So she was gratified, even exhilarated, to report that sales in the industrial town of Barre, Vermont, equaled those in posh Northeast Harbor. Purchases by servants and modest folk at the fancier spots were another plus for the Caravan’s real, social purpose.”

Once the Caravan was retired from commercial use, it was given a new life as a public library bookmobile in upstate New York.

The Simmons Connection

In 1932, Bertha Mahony married William D. Miller, a furniture manufacturer who lived in Ashburnham, in central Massachusetts. Mahony and Whitney (by then married, herself) resigned from the Bookshop in 1934 to concentrate on The Horn Book. They assumed ownership of the magazine with their husbands, along with printer Thomas Todd. Mahony continued as editor of The Horn Book until 1950, and remained an active participant in the publication until her death in 1969.

From its inception, connections between The Horn Book and Simmons have remained consistent. Former Horn Book Editors Paul Heins and Ethel Heins (who each received Honorary Doctor of Children's Literature from Simmons in 1985) were instrumental in the founding of the Center for the Study of Children’s Literature at Simmons and taught in the Master’s program for its first decade. Another former Horn Book Editor, Adjunct Professor Anita Silvey, has taught at Simmons for more than 25 years.

Aside from Gershowitz, the current staff roster includes Managing Editor Cynthia K. Ritter ’10MA, Associate Editor Shoshana Flax ’09MFA, and Contributing Editor Martha V. Parravano ’88MA. This year, Professor and Program Director Cathryn Mercier (who worked at Horn Book before coming to Simmons in 1985) is Chair of the 2024 Boston Globe-Horn Book Award Committee. Of this position, Mercier said, “I am particularly honored, knowing that the Horn Book was founded by a Simmons alumna!”

Mahony did not imagine the impact the magazine would have on the world of children’s literature. As she wrote in that first editorial letter: “Lest this horn-blowing become tiresome to you or to us, we shall publish The Hornbook only when we have something of real interest to say; not oftener than four times a year.”

Gershowitz feels the statement belies her intense commitment to the subject. “It’s a lighthearted way to introduce something that ends up lasting 100 years,” she says. Since the 1930s, the magazine has been published six times per year.