On January 19, Simmons’ Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (ODEI) hosted “Islamophobia in the United States: Understanding Past and Present Anti-Muslim Discrimination,” a virtual lecture by Associate Professor of Sociology and Director of Research for the Institute of Social Policy and Understanding Saher Selod. This talk chronicled the history of anti-Muslim racism and demonstrated how 9/11 instituted a new era of the racialization of Muslims.

“I would like to help contextualize what many of you might not understand, in terms of what is happening in this current moment [with the Israel-Hamas War],” began Saher Selod, Associate Professor of the Sociology Department and Faculty Affiliate for the Center for Security, Race, and Rights at Rutgers University. Presented to Simmons faculty and staff, Selod’s lecture, “Islamophobia in the United States: Understanding Past and Present Anti-Muslim Discrimination,” traced the evolution of racist attitudes and policies toward Muslims, particularly Muslims residing in the United States in the immediate aftermath of 9/11. Marshaling abundant sources — visual arts, popular press, films, postcolonial theory, quantitative data, legislation, and judicial documents — this lecture drew upon Selod’s first book, Racialized Surveillance: Muslim Americans in the War on Terror (Rutgers University Press, 2018), and her forthcoming book, co-authored with Inaash Islam and Steve Garner, A Global Racial Enemy: Muslims and Twenty-First Century Racism (Polity, 2024).

Historicizing Islamophobia

Selod’s area of scholarly expertise resonates with her on a personal level. She began her doctoral studies just two years before September 11, the first major terrorist attack on U.S. soil. In the event’s aftermath, she recalls seeing slogans that read “United We Stand” and “Never Forget.” As Selod explains, “Although anti-Muslim racism and Islamophobia had existed previously, things changed drastically after 9/11. In my [Muslim] family, it was a stark moment. For Muslims living in the United States, there was a notable difference between pre-and post-9/11.” For Selod, “anti-Muslim racism is an example of twenty-first-century racism because we see the construction of Muslims being used to create counter-terrorism laws and policies across the globe.”

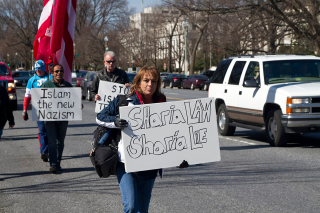

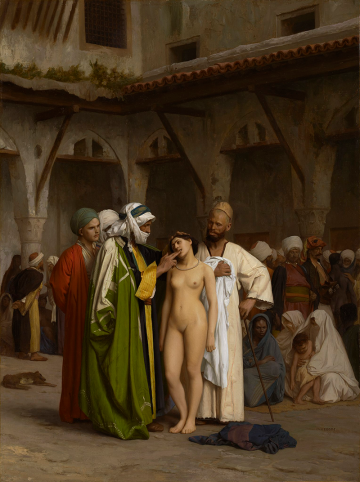

In the first half of her talk, Selod chronicled the racialization of Muslims and the forging of Islamophobia before September 11. She spotlighted postcolonial scholar Edward Said (1935–2003) and his groundbreaking 1978 book Orientalism, which reveals how the knowledge and representations of Arab cultures and societies were in fact fabricated by seventeenth and eighteenth-century Europeans who never set foot in those parts of the world. For instance, European painters who adopted an “orientalist” style depicted Muslim and Arab men as brutish and misogynistic, whereas women appeared servile and exploited. “Said claimed that these stereotypical representations were tied to colonial interests, and could be wielded to justify colonial exploits,” explained Selod.

To support her argument concerning the racialization of Muslims and other religious minorities in the United States, Selod turned to the history of U.S. citizenship. The Naturalization Act of 1790 evidently limited citizenship to free, white men. Selod examined the case of Bhagat Singh Thind (1892–1967), an Indian American writer and World War I veteran who practiced Sikhism. Thind’s initial attempts to obtain citizenship were ultimately denied. The U.S. Supreme Court (from the United States vs. Bhagat Singh Thind, 1923) determined that “the physical group characteristics of Hindus render them readily distinguishable from various groups of persons in this country commonly recognized as white.” From this ruling, Selod deduced that “In this country, religion was used to racialize people who were non-white.” (Upon his third attempt at naturalization in 1935, Thind was successful, largely due to the Nye-Lea Act, which rendered World War I veterans eligible for naturalization regardless of race).

According to Selod, “race-ing religion,” specifically Islam, became more prominent after the Iran Hostage Crisis (1979–1981). “Here we start to see the transition from anti-Arab to anti-Muslim attitudes circulating within the United States. Our media and government played a significant role in popularizing anti-Muslim rhetoric.”

Beyond politics and policies, Selod analyzed how popular culture shaped and reinforced harmful stereotypes of Muslims. For example, the cult classic Back to the Future (1985) contains a scene with an unidentified Arab terrorist speaking in gibberish (i.e., not proper Arabic). Moreover, a 2022 study released by the USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative found that only 1.1% of characters in recent television series are Muslims. (By comparison, Muslims constitute nearly one-fourth of the world’s total population). Onscreen, Muslim characters are frequently depicted as violent perpetrators or the victims of violence.

“These caricatures of Muslim individuals fortify further longstanding stereotypes of Islam as an antiquated, belligerent, undemocratic, and misogynist religion,” said Selod. “But in reality, Muslims comprise a very racially, religiously, and culturally diverse group.”

Racializing Muslims in the Twenty-First Century

The second half of Selod’s talk focused on Islamophobia post-September 11. She discussed how twenty-first-century governmental policies, federal agencies, and counterterrorism tactics — although formed in the interest of national security — ultimately vilified and racialized Muslims in unprecedented ways. For instance, the USA Patriot Act (2001) increased the government’s capacity to surveil non-citizens (and now select citizens), the Department of Homeland Security (formed in 2002) strengthened customs, border, and immigration enforcement, and the Transportation Security Administration (TSA, formed in 2001) heightened airport security. The Terrorism Screening Center’s No-Fly List (initiated in 2001) imposed further restrictions on Muslims’ traveling and personal freedoms.

The National Security Entry-Exit Registration System (NSEERS, formed in 2011 and expired under President Barack Obama), gestured toward the criminalization of Muslims. As Selod explained, “Under NSEERS, if you were a non-citizen or male aged 16 or over from one of the 25 blacklisted countries [24 of which were Muslim-majority], you would have to register with the government. During the registration process, you would be interrogated, had your photograph taken, and were fingerprinted. Thus, after 9/11, Muslim citizens in this country were being targeted for surveillance.” She added that in the immediate post-September 11 era, the FBI visited and interrogated Muslims, including her own father.

“Surveillance is not color blind but it targets specific racialized hues that include phenotypes [observable characteristics], as well as culturally-specific clothing, language, and so forth — particularly for Muslims of the United States.” Selod also unpacked the discriminating and humiliating nature of TSA procedures, which have involved Muslim women being asked to remove their hijabs. “Security is performative, it is something to be enacted,” Selod observed. “It is demonstrative, it is performative, but it is not in the service of something being more secure. . . surveilling Muslim men and women makes us [the government] feel secure while it criminalizes and racializes others.”

Advocacy, Education, and Allyship

Selod concluded her lecture by emphasizing key organizations working to combat Islamophobia. The Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU) — where Selod serves as Director of Research — performs advocacy work and generates research that counters anti-Muslim hate, educates people about Islam, and supports inclusive dialogues and decision-making. “And in the media,” Selod adds, “the television miniseries Ms. Marvel (2022) gave us our first Muslim hero.”

Despite the many obstacles Muslims face and the geopolitical conflict of our current moment, Selod noted progress. “When people come together and do this advocacy work, it is good for everybody. . . Data from the ISPU indicates that Islamophobia is universally bad, as it correlates with increased support for authoritarianism, the hyper-policing of migrants and BIPOC individuals, and so forth. We need to identify Islamophobia as a form of racism, and acknowledge that its persistence does not serve anyone well.”

During the post-lecture discussion, Selod spoke about supporting Muslims within the Simmons community. “Being an ally could be something very basic, like walking with your Muslim friends to the dorms or other destinations so that they feel safe.”

For Dr. Nakeisha Cody, Director of Undergraduate Research and Fellowships who moderated this event, open dialogues about Islamophobia can help “push the mission forward” at Simmons. “This discussion provides meaningful dialogue and a space for learning that allows us to. . . create an inclusive environment and support our students.”

The discussion concluded with an expression of gratitude. “I am really grateful for the work that our [Simmons’] administration is doing. . . they are very open to hearing about Muslims and anti-Muslim racism, and incorporating this into their larger DEI initiatives,” said Selod. “Like all other diversity work, we need to combat Islamophobia in a sustained fashion, not just in moments of crisis.”

Recommended resources from Dr. Selod (concerning Islamophobia, anti-oppression research, and advocacy)

- Countering and Dismantling Islamophobia: A Comprehensive Guide for Individuals and Organizations

- How US Muslims Have Transformed Since 9/11 (cites Dr. Selod)

- The Global Rise of White Supremacist Terrorism

- “Islamophobia and Public Health in the United States,” by Goleen Samari, PhD, MPH, MA

- A powerful detainment story from New York Public Radio’s On the Media

- The Simmons Library Anti-Oppression Research Guide (currently being reviewed and updated)

- “Discrimination, Life Stress, and Mental Health Among Muslims: A Preregistered Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” by Ummul-Kiram Kathawalla and Moin Syed