This June, Professor Marilisa Jiménez García received the Children's Literature Association's annual book award for her 2021 monograph, Side by Side. In this text, Jiménez García explores youth literature and culture as a means to comprehend the complex contours of power relations between Puerto Rico and the United States.

When Associate Professor of Children's Literature Marilisa Jiménez García received the 2023 book award from the Children's Literature Association, she saw it as a win for her community. "I immediately started getting congratulations from all the Puerto Rican writers and colleagues who were a part of my journey," she says. "It felt more like we won, rather than I won."

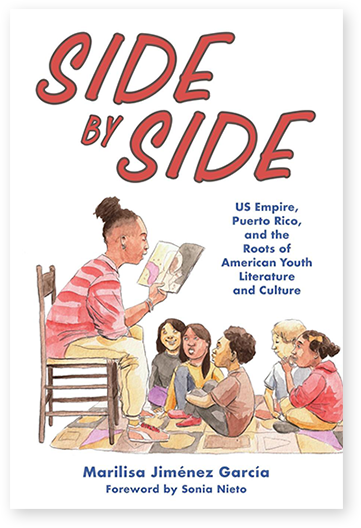

Her book, Side by Side: US Empire, Puerto Rico, and the Roots of American Youth Literature and Culture (University Press of Mississippi, 2021), is the first extensive study of Puerto Rican and diasporic writers of youth literature over the 20th century.

The phrase "side by side" refers to the peculiar power dynamic that constituted the colonial relationship between the U.S. and Puerto Rico, which became embedded in youth literature. In other words, this rapport is both functional and dysfunctional, close and distant. Like many Puerto Ricans, Jiménez García sees the country as a kind of "legalized colony" that the U.S. lords over in a supposedly benign way.

Jiménez García writes in her book that "representations of closeness and universality in youth literature and culture are often a guise for colonial violence and tie to deeply embedded, interrelated notions in US culture about race, literacy, embodiment, language, and, ultimately, citizenship."

Throughout the text, Jiménez García makes a strong case for the importance of youth literature and culture concerning Puerto Rico. Children's books, she reports, were one of the earliest written sources that imagined the power and racial relations between the U.S. and Puerto Rico following the Spanish-American War (1898), which resulted in America's takeover of Puerto Rico from Spain, its first colonizer. Jiménez García finds that early literature by white authors (circa 1890s–1960s) presented Puerto Ricans as a submissive, colonized Other, whereas in subsequent decades, Indigenous and diasporic Puerto Rican writers spun tales of resistance and revolt.

Side by Side analyzes a wide variety of children's literature and media, including primers, animal fables, and television programs. Moreover, Jiménez García prioritizes female writers and writers of color.

The first chapter examines primers from the early twentieth century. In these texts, white authors depict Puerto Rican children as vagrant, troubled, and dependent upon the white community. Jiménez García argues that these artifacts of children's literature belonged to a larger colonial project that championed the U.S. as a benevolent imperial force and caricatured Puerto Ricans as passive and subservient subjects.

In response, Puerto Rican authors re-wrote the master narrative of U.S.-Puerto Rican relations in empowering ways. Pura Belpré (1899–1982), the first Puerto Rican librarian in New York City, emerges as a key figure for Jiménez García. Belpré, who was of Afro-Boricua descent (i.e., a Puerto Rican with African ancestry), promoted folklore and storytelling. In this way, she created a "living archive" for people of color. Belpré's own literature resisted U.S. colonialism by highlighting trickster figures and victorious underdogs.

Within the context of Belpré's work, Jiménez García invokes the concept of "restorying." Here restorying functions as a strategy to recover the past and re-imagine the present. From the Puerto Rican perspective, restorying creates a sense of ownership and helps empower youth. By reviving the stories of Puerto Ricans' ancestors, authors like Belpré testified to mixed-race survival against the historical backdrop of conquest and colonization.

Jiménez García locates another aspect of Puerto Rican resistance in the popular children's television program Sesame Street. The character of Maria (played by Sonia Manzano), demonstrates the powerful presence of the Puerto Rican diaspora in New York. Jiménez García analyzes how Manzano's character gives voice to an underrepresented community by engaging multilingual discourse and challenging racist stereotypes. In one episode, Maria teaches Elmo how to salsa; according to Jiménez García, these moments celebrate multiculturalism and embodied knowledge.

In conclusion, Side by Side shows how Puerto Ricans demonstrate agency and resilience in times of disaster, namely Hurricane Maria (2017) and the country's economic collapse. Jiménez García turns to literature and musical theater to exemplify how Puerto Ricans survive unforeseen catastrophes by embracing their culture and their stories.

One of the key insights of Side by Side is that marginalized cultures transmit their history through (oral) storytelling, but not necessarily via written texts. Jiménez García credits this line of thinking to New York University scholar Juan Flores (1943–2014). "I love the writing of sociologist Juan Flores, who was the first Puerto Rican scholar I read in graduate school. He gave me frameworks to do the kind of work that I do," says Jiménez García. "Consider the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Maria. What do we do if we have no books, or no regular access to books? How do people survive and carry their stories and traditions through art, storytelling, and so forth? Because of their proximity to children, storytellers (many of them women) were undermined as ‘sweet' and not seen as scholars."

Jiménez García intends for her monograph to supplement and, ultimately, challenge the master narrative of U.S. history. "Empire is as old as time," she says, "and you don't learn this history in school. Moreover, most students do not learn about non-continental U.S. history, like that of the Philippines, Puerto Rico, or even states like Hawaii and Alaska. But you learn so much about your own history when you learn about these smaller spaces that make up the whole."

Jiménez García feels that her greatest satisfaction derives from the Latina community that the book brought together. "Writing certain things can create community," she says. "Finding Puerto Rican authors who are doing this work, and co-creating a history about it was immensely gratifying for me."

Jiménez García's newest book, She Persisted: Pura Belpré, a children's chapter biography co-authored with Meg Medina, was just released with Penguin Random House in September. Additionally, she is working on a new book project on ethnic studies and its impact on youth literature. Co-edited with Sonia Alejandra Rodriguez, Ethnic Studies and Youth Literature: A Critical Reader (SUNY Press, forthcoming) reimagines the concept of U.S. empire in various contemporary contexts, including recent book bans. Currently, Jiménez García is also researching Florida history that was taught in schools during the 1980s and '90s.

As a Latina scholar of Latinx studies, a drive toward decolonization runs through all of Jiménez García's scholarship. "True decolonization is a political act that involves policies, land, and people." (Here she agrees with Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang's seminal 2012 article, "Decolonization is Not a Metaphor.") Jiménez García explains that "to me, decolonization demands sovereignty and self-determination. However, it can also be intellectual, like having Latina/Latino professors at universities who bring valuable perspective and methods to Latinx studies. While education does not replace deliberate acts of decolonization, it can empower decision makers in those communities. Therefore, the work I do performs a kind of intellectual sovereignty."